You are hereNewspapers 1970-1979 / Erle Stanley Gardner

Erle Stanley Gardner

Perry Mason's Creator

LIFE EXCELLING ART

Erle Stanley Gardner

Erle Stanley Gardner

By TOM SOTER

from THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

March 24, 1978

"I still have vivid recollections," said mystery writer Erie Stanley Gardner some years ago, "of putting in day after day trying a case in front of a jury – which is one of the most exhausting activities I know about – dashing up to the law library after court had adjourned to spend three or four hours looking up law points with which I could trap my adversary the next day, then going home, grabbing a glass of milk with an egg in it, dashing upstairs to my study, ripping the cover off my typewriter, noticing it was 11:30 p.m., and settling down with grim determination to get a plot for a story. Along about three in the morning I would have completed my daily slint of a 4,000-word minimum and would crawl into bed."

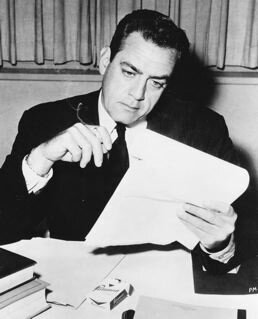

Erie Stanley Gardner, of course, is the creator of world-famous lawyer Perry Mason, and this anecdote helps explain how Gardner, by the time of his death eight years ago this month, had become the best-selling, arid most prolific American writer of the 20th century, with paperbacks selling at the rate of 20,000 a day and all-time sales, as of 1977, nearing 304,000,000 copies in 23 languages.

Like Walter Scott and Daniel Defoe before him, however, Gardner was a man superior to his fictions: cleverly plotted, easily read formula pieces that are heavy on story and not much else. To say that he led a varied life would be as much an understatement as saying that he was concerned with justice and the underdog. Erie Stanley Garnder was a man fascinated by people-in all classes of society-and he spent his life searching them out, helping them when he could and, most importantIy, learning from them. His boyhood was spent in the Klondike, where his father was a miner, and his education was, by his own account, "unorthodox, gravitating between amateur, four-round exhibition fights at Oroville, Calif., to studying law in the office of the deputy district attorney."

Although he was admitted to the California Bar in 1910 and practiced law in Oxnard, Calif. for the next six years, the young man could not settle down to anything conventional. He defended penniless Chinese and Mexican workers when no one else would help them (and many were acquitted); gave up law for a couple of years to become a tire salesman; joined a law firm, and then, in 1921, with a story called "The Police and the House," began writing for pulp magazines. This was the turning point, and by 1928 he averaged better than a million words a year while still maintaining. his law practice.

In the 1930s, Gardner began writing full time. He also began traveling. "I have always been fascinated by the Chinese people," reported the author in 1942; "and because I had numerous Chinese clients, started studying the language and psychology." This led to a trip to China in 1931, followed by journeys to Horiolulu, the South Seas, Mexico and various parts of the United States. Gardner was a man of seemingly limitless energy and curiosity and his travels were as frequent as his books.

Such a life was made possible with the advent of Perry Mason. The lawyer-detective, who ultimately starred in 82 novels, a dozen short stories, six movies, 302 television episodes and countless radio shows, first appeared in The Case of the Velvet Claws in 1933. It was apparently turned down by a number of publishers before being accepted by Thayer Hobson, president of William Morrow & Co., who suggested'that Gardner specialize in a series character rather than create new heroes and new locales for each adventure.

Raymond Burr as Perry Mason

The format suited the author and, so, when he died on March 11, 1970, Gardner was literally earning millions by producing, with the help of a battery of tape-recorders and transcribers-four or five novels a year. "Thirty years ago," he reminisced in 1968, "I could dictate a book in a week or ten days, revise and polish it and get it into the hands of a publisher within two or three weeks of the time I started."

Among the many books and countless series characters and also countless pen names: the Patent Leather Kid, Hard Rock Hogan, Ed Jenkins, The Phantom Crook, Bertha Cool and Donald Lam, D.A. Doug Selby, and, of course, Perry Mason. Among the pen names were A. A. Fair, Charle'S M. Green, Kyle Corning, Grant Halliday, Carleton Kendrake and Arthur Mann Sellers. In total, he wrote close to 150 books.

Gardner once explained his popularity:"Ordinary readers see in me somebody they can identify with. I'm for the underdog. When you realize that since prohibition, since rationing in World War II, since the income tax, the average man goes around, with a vague sense of uneasiness. He wants to be reassured that there is an advocate who will defend him and get him off? Perry Mason is that kind of lawyer, a combination of three or four I've known, maybe a little of me. "

There was ,more than just a little bit of Gardner in Mason. The author's concern for fair play, which never left him, was even stronger than his creation's. He was an ardent sportsman, for instance, yet he refused to use a gun. He felt that wildlife didn't have a chance against high-powered weapons – and so he hunted with a bow and arrows. More significantly, in 1948, he helped found "The Court of Last Resort," intended to help poor men who had been wrongfully convicted of murder and who had exhausted all their legal rights. The court was successfully maintained – with many clients being cleared – for fifteen years, and in that time, "just about every hopeless case in the United States was dumped on me," Garciner once commented. In his later years, the author's interest in the downtrodden continued, as did his writing. When he died pe left two unpublished Perry Mason novels sitting in his drawer.

More significantly, in 1948, he helped found "The Court of Last Resort," intended to help poor men who had been wrongfully convicted of murder and who had exhausted all their legal rights. The court was successfully maintained – with many clients being cleared – for fifteen years, and in that time, "just about every hopeless case in the United States was dumped on me," Garciner once commented. In his later years, the author's interest in the downtrodden continued, as did his writing. When he died pe left two unpublished Perry Mason novels sitting in his drawer.

Seven months before his death, while on vacation, I sent Gardner birthday greetings. Busy as he was, he didn't have to reply; but being Erie Stanley Gardner, he did. "I had a bang-up birthday,'" he wrote me, "and your letter certainly added to my enjoyment. Thanks a lot for remembering me, and I hope you had a wonderful vacation."

Remembering others was something Gardner did so well. It is fitting, then, that we now remember not only the books, but more importantly, the man who wrote them. "Most readers are beset with a lot of problems they can't solve," Gardner once said. "When they try to relax, their minds keep gnawing over these problems and there is no solution. They pick up a mystery story, become completely absorbed in the problem, see it worked out to a final and just conclusion, turn out the light and go to sleep. If I have given millions that sort of relaxation, it is reward enough."